Architecture and Evolution: III. Ornament

Like symmetry, ornament has been a principal feature of architecture throughout history, until modernism rose to significance. Ornament can be found in all human civilisations. Even in relatively primitive societies, such as African and Germanic tribes, it can widely be found on pottery, weaponry and clothing.1 As with symmetry, its value lies in its appeal to our evolutionarily formed aesthetic preferences.

The historical argument is equivalent to the one used in the previous chapter. Since the popularity of ornament spans all historical civilisations, we can deduce that its appeal lies in our nature. It therefore stems from our evolutionary history. There are many reasons why this could be.

One possible explanation is that human structures are relatively new in the evolutionary history of our species, and that we have evolved to become uncomfortable or stressed when seeing structures that were not benign during this time. Buildings are therefore in principle perceived as unnatural or difficult to analyse and thereby a potential threat, unless they are decorated with forms that are not perceived as such. From this the value of ornament could stem, especially ornament containing natural forms.

From the history of ornament it can be seen that specific types of ornament possess special universal popularity. Considering the above from an evolutionary psychological perspective, one can see why that is. Forms that were present in nature and benign in our evolutionary history, should in theory be subconsciously perceived as natural, as opposed to abstract forms or forms such as tools or vehicles. Moreover, the special popularity of these types of ornament is congruent with empirical findings in neurology and psychology, which have shown that we viscerally respond to unnatural forms, for the potential threat that they were in our evolutionary history.2

Foliage

The depiction of foliage has played a central role in ornament throughout history and in virtually all civilisations. The ancient Egyptians used to adorn their walls and the capitals of their pillars largely with simplistic depictions of foliage and flowers (Figure 3.1). Likewise, foliage plays a large role in Roman ornament as well. The well-known Corinthian capital, which originated in ancient Greek civilisation, consists of a symmetrical layout of acanthus leaves, topped by spirals and a flower (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1. Symmetrically placed, foliage-shaped ornaments on the capitals of Egyptian columns.

Figure 3.2. A drawing of the Corinthian capital and base of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, containing shapes of acanthus leaves, a flower and spirals, all positioned symmetrically.

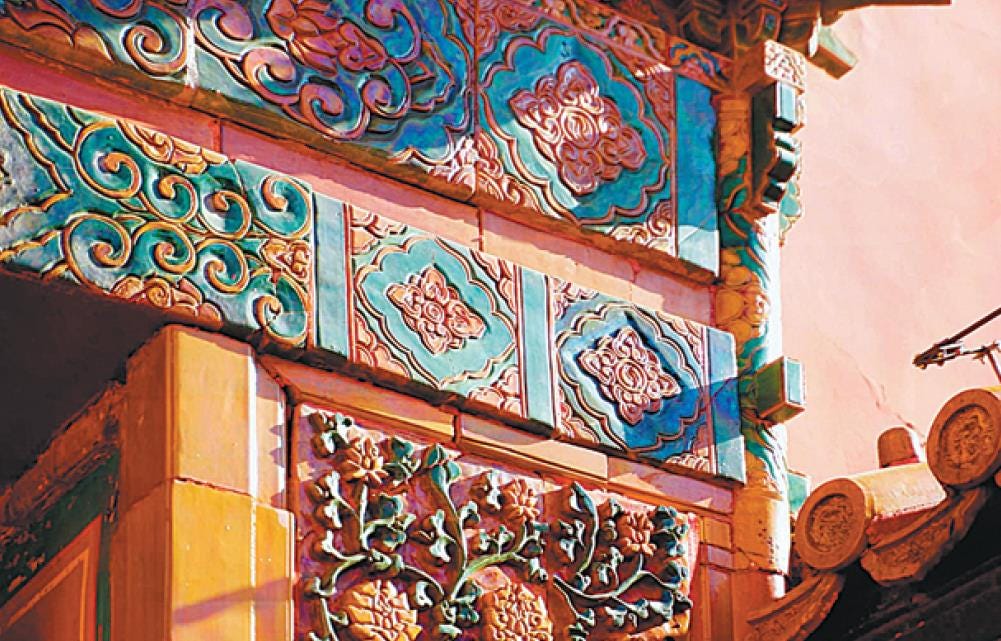

As mentioned, the aesthetic preference for foliage exists across all human civilisations. In China (Figure 3.3), depictions of foliage can widely be found in ornament as well. There exists one exception, across the ocean, in ancient Mayan civilisation. It is difficult to tell whether foliage was popular there as well since Mayan ornament was relatively unrealistic and simplistic. Besides, not much of their architecture is left.

Moreover, what we know of Native American ornament is that it is very simplistic, unrealistic and imperfectly made. This can be found in primitive African ornament as well, which involves similarly exaggerated facial features in its depictions of faces as well. An explanation could be that artists in these tribal societies were not sophisticated enough to copy the natural world around them. The techniques for doing so may not have existed there yet. We therefore cannot conclude that this falsifies the universal value of foliage as an ornament. Another factor may be at play.

Figure 3.3. A Chinese wood carving in the shape of foliage and flowers.

However, in all technologically and artistically advanced societies throughout history, foliage played a prominent role in ornament. Even in Muslim civilisations, where the depiction of animals and plants was prohibited by Islam, ornament involving foliage has persisted (Figure 3.4). Citing James Ward, historian and writer of the book Historic Ornament:

‘The originality of the latter arose from the experimenting in ornamental patterns that should have no likeness to plants, animals, or other natural forms. This prohibition of the use of objects from nature in their ornament was one of the articles of the Moslem religion; but to get any pleasing variety in ornament and leave out all natural reminiscences in the designs is out of human power, so consequently we have, even in Saracenic ornament, natural forms put through a geometrical process of draughtsmanship. Saracenic ornament in what is sometimes called Arabian has leaf and bud-like forms interlaced with strap-work, which is often very beautiful and is known under the name of “Arabesque”.’

(James Ward, Historic Ornament, published in 1897)

Again, as with symmetry and ornament in general, foliage as ornament possesses an evolutionarily formed appeal. Our aesthetic preference for it is in our nature.

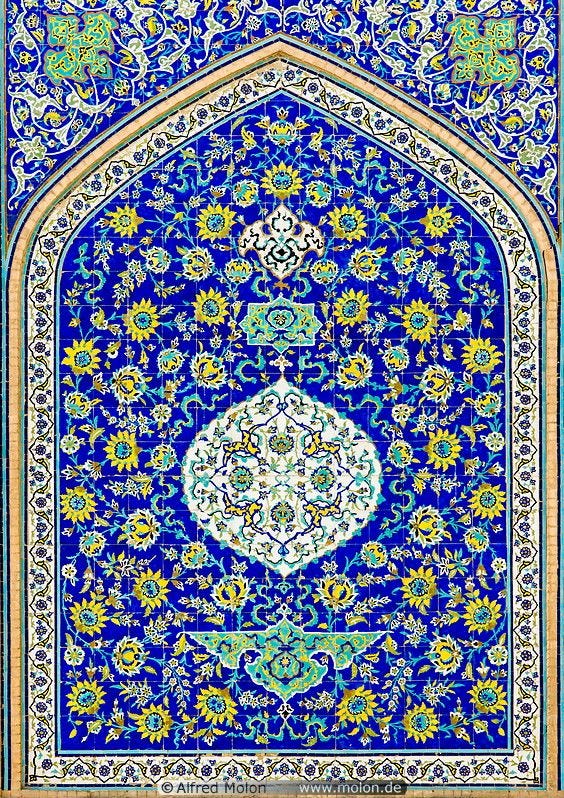

Figure 3.4. Ornament in the shape of foliage and flowers in the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in Esfahan, Iran.

Flowers

Flowers are a peculiar human universal. They are inedible, nor have they otherwise been useful to humans in most of our evolutionary history. Yet their appeal is very strong, not only in ornamentation. Across the entire world, flowers are bought for their beauty and are used as romantic gifts. Often combined with foliage, they decorate gardens, interiors and are a popular subject for wallpapers and paintings. The global flower market is expected to grow to approximately $79 billion dollars yearly.3 Flowers have always played a special role in human civilisation.

It is not difficult to show the ubiquity of floral patterns in architecture, especially in interiors. In fact, it is quite evident from the images in this article. Floral ornament is used in many of the world’s most beloved buildings, whether it is our own home, the palace of Versailles (Figure 3.5), the Taj Mahal (Figure 3.6), the Sheikh Lotfollah mosque in Esfahan, Iran (Figure 3.7) or the Forbidden City in Beijing, China (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.5. The Queen’s Apartment in the Palace of Versailles, France. Its walls and furniture are adorned with beautiful, highly realistic floral patterns and symmetrical floral ornaments.

Figure 3.6. A symmetrical floral ornament in the Taj Mahal, India.

Figure 3.7. A symmetrical ornament, containing flowers and foliage, in the Sheikh Lotfollah mosque in Esfahan, Iran.

Figure 3.8. Floral ornament in the Forbidden City, Beijing, China.

As with ornament in general and with foliage, our aesthetic appreciation of flowers is the result of evolution. Citing Lisa Duchene, writer of the article ‘Probing Question: Why Are Flowers Beautiful?’ published in Penn State News:

‘People love flowers for their array of colors, textures, shapes and fragrances. But is pleasing the human eye the purpose of nature's floral design?

Hardly. Survival is the plant's top priority, reminds Claude dePamphilis, a Penn State plant evolutionary biologist and principal investigator of the Floral Genome Project.

"The beauty of the flower is a by-product of what it takes for the plant to attract pollinators," says dePamphilis. "The features that we appreciate are cues to pollinators that there are rewards to be found in the flower."

Scent, color, and size all attract a diversity of pollinators, which include thousands of species of bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, and beetles, as well as vertebrates such as birds and bats.’

(Lisa Duchene, ‘Probing Question: Why Are Flowers Beautiful?’, 21 January 2008, Penn State News)4

Again, as with the human universals discussed before, one is safe to conclude that flowers possess universal beauty. Our evolutionary history has given us an ardent, innate love for the beauty of flowers. Yet it is not only in architecture that flowers play a prominent role. In fact, the beauty of flowers is of such intensity that they widely serve as a romantic gift. Their uplifting power has also given them prominent roles as the principal decorative elements at weddings and funerals. No other type of object enjoys such status.

Animals and Humans

Another human universal in the domain of ornament is the depiction of humans, animals and mythical beings. The latter are often blends of life forms, such as the centaur, which is half man, half horse.

Often, the same animals are depicted in different cultures and in different ways, such as the lion. A comparison between these different versions of the same animal provides an interesting insight in how styles differ across cultures and geographies. It also shows how some cultures have more sophisticated artistic techniques than others.

Figure 3.9. A lion sculpture in Florence, Italy.

Figure 3.10. A Chinese ‘guardian lion’. Less realistic, more mythical and in a way more ornamental than its European counterparts.

Figure 3.11. A depiction of a growling lion’s head.

Animals and humans have always been a principal subject of ornament. Prehistoric cave paintings, which are regarded as the first examples of human ornament, depict humans and animals as well as crossover forms. Whether the depiction of animals and humans only carries symbolic value or also ornamental value, cannot be deduced from history. However, the depiction of animals and humans in ornament can often be found in contexts wherein these depictions do not ‘tell a story’ or convey a message otherwise. We could therefore say it is highly likely that these do indeed have universal ornamental value, stemming from our nature. Moreover, figures and animal representation, although forbidden in Islam like the representation of foliage, was practised by Saracen sculptors.5 And in classical architecture and art, human figures boast attractive bodies and faces made to appeal to the sexually active species that we human beings are.

Figure 3.12. A mosaic in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, containing humans and serpents and surrounded by a border of foliage.

Figure 3.13. A lavishly ornamented gable in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. On both sides, it contains muscular human figures, representing Neptune (left) and Mercury (right). Note how they are positioned in a way that shows their lean muscles (i.e. their most attractive features) well, which is very visible in their legs.

These figures are likely to have been built with a symbolic meaning in mind, since Neptune is the god of the seas and Mercury the god of travel and commerce, both fitting the Dutch republic’s role as centre of world (naval) commerce at the time. At the United East India Company’s peak, it boasted a merchant fleet larger than that of any other country.

Note as well the use of symmetry and foliage in its design. This gable is clearly made to appeal to our innate aesthetic preferences in many ways.

Spirals

There also exist abstract shapes which seem to possess universal aesthetic value. One of these is the spiral. They served as decorations Germanic tribes used to put on shields, pottery and other tools6 and they are a staple in baroque architecture, art nouveau and in many floral and foliage patterns around the world. Whether its appeal is due to its intrinsically curved shape, because of its mathematical characteristics or because it has been a natural shape in itself, is unclear. But its ubiquity across the different continents does imply it possesses universal aesthetic value stemming from our nature.

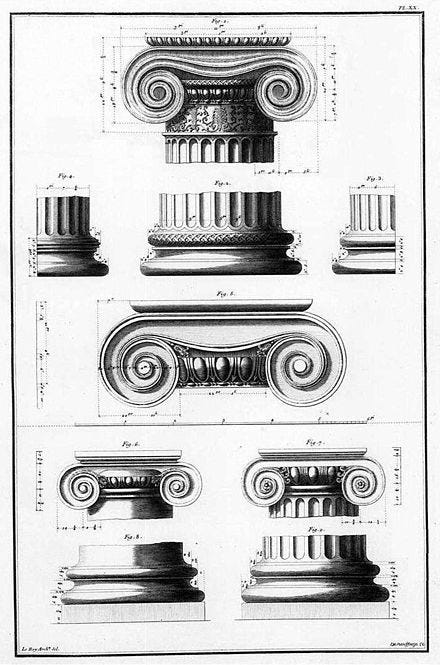

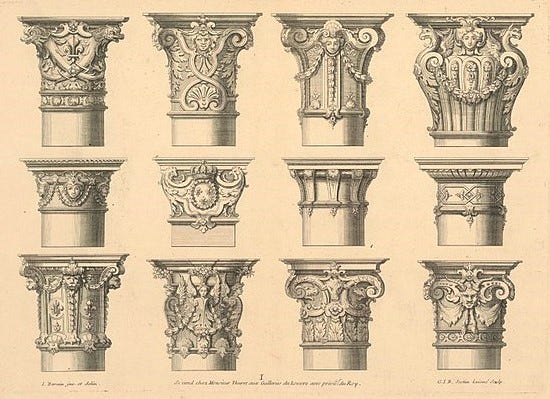

Spirals can be found in Corinthian (Figure 3.2) and Ionian (Figure 3.13) capitals and many baroque capitals (Figure 3.14). It can also be found in many depictions of hair, such as in the Chinese guardian lion in Figure 3.10. They are a popular shape in designing consoles as well (Figure 3.16).

Figure 3.14. Designs and proportions for an Ionian column.

Figure 3.15. Illustrations of Baroque capitals from France, in the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. Many of these contain spirals like the Corinthian and Ionian capitals. Note their symmetry and the large presence of foliage and human faces.

Figure 3.16. A console containing two spirals, foliage and a lion’s head. Note its symmetry when viewed from the front.

Figure 3.17. A Roman mosaic depicting the ‘Vitruvian wave’ pattern in Vaison-la-Romaine, France.

Curves

Curves are proven to have a stress-reducing effect on the viewer. Citing Ann Sussman, writer of Cognitive Architecture:

‘In terms of innate preference for shape, humans also have a clear bias for curves over straight or sharp lines. Aesthetic judgments are a complex matter engaging many part of the brain. Studies in the field of aesthetics more than a century ago found that when it comes to 2D and 3D objects, curves elicit feelings of happiness and elation, while jagged and sharp forms, tend to connect to feelings of pain and sadness …

… Curves are in general felt to be more beautiful than straight lines. They are more graceful and pliable, and avoid the harshness of some straight lines,” psychologist Kate Gordon wrote in her book Esthetics, published in 1909 (Gordon: 169). Even “the most simple abstract line… may have an emotional effect and meaning of its own. (Gordon: 160).” Numerous psychology research papers have documented these findings since…

…The impact of our preference for curves transfers to our feelings about architecture according to a more recent study using fMRI, psychologist Oshin Vartanian and colleagues (2013) determined. In this test, twenty-four subjects were given 200 pictures of architectural spaces to look at. Half of the images were rectilinear; half curvilinear. “As predicted, participants were more likely to judge spaces as beautiful if they were curvilinear than rectilinear,” the report said (Vartanian et al. 2013: 1). “The results suggest that the well-established effect of contour on aesthetic preference can be extended to architecture. Furthermore, the combination of our behavioral and neural evidence underscores the role of emotion in our preference for curvilinear objects in this domain.” (Vartanian et al. 2013: 1). We like things plump and round. Why does the curve-bias exist? Humans evolved to assess their environment quickly. Pointed shapes, such as barbs, thorns, quills, sharp teeth, were everpresent threats in our evolutionary past, so it was advantageous to sense them fast and be able to flee if one had to. Psychologically, part of our brain still feels a lion could be at the gate, even as we sit in the living room of a high-rise or suburban tract house. We evolved for this past environment, and are still designed for it whether or not it exists in our present.

“Humans like sharp angled objects significantly less than they like objects with a curved contour,” wrote neuroscientists Moshe Bar and Maital Neta in a 2007 paper summarizing a study that scanned participants as they observed more than 200 different shapes. “This bias can stem from an increased sense of threat and danger conveyed by these sharp visual elements.” The researchers noted an area of the brain engaged in the fearful responses, the amygdala (sometimes called our ‘lizard brain’), “shows significantly more activation for the sharp-angled objects compared with their curved counterparts.” They also proposed “that the danger conveyed by the sharpangle stimuli was relatively implicit.” It appears, then, we do not even have to learn much about some things, part of our brain is set up to have us run from a sharp shape.’(Ann Sussman, Cognitive Architecture)

As Ann Sussman makes clear in her book, there exists an innate preference for curves as opposed to sharp angles. This fact could explain to a great extent why many historical architectural styles involved many curves, such as the baroque and art nouveau. Especially the rococo style, which contains many abstract, curved adornments, is likely to have earned its appeal from its curved forms.

The universal appeal of curves could also perhaps explain that of spirals. Evidence to the contrary does exist, however, such as the popular angular ‘spiral’ patterns that originated in Greek architecture.

Well-defined boundaries

The last human universal in the domain of ornament addressed in this article is the concept of ‘well-defined boundaries’. A keen eye would have noticed that many of the ornamental planes in this article’s illustrations contain boundaries. The ornamental planes in Figures 3.3, 3.4, 3.8 and 3.12 all contain well-defined borders surrounding them. These borders all contain ornamental patterns themselves as well.

There appears to be a universal aesthetic preference for this phenomenon as well, which appears to exist because well-defined boundaries make the analysis of an object easier to process for the viewer’s mind. Since the ease and speed of analysing structures has been a matter of evolutionary importance, we are evolved to feel more comfortable when structures possess characteristics that make them easy and quick for the mind to process.7 This neurological-evolutionary factor also appears to cause our preference for symmetries.

Other potential attractors

Colours that can be found in natural foods could possibly be found beautiful because attraction to those objects provide an evolutionary advantage.

Nutritional fruits and vegetables, for example, have evolved to be found attractive. Fruits and vegetables that are more likely to be eaten by humans and animals spread their seeds more effectively, thereby become more prevalent. On their part, humans and animals have also evolved to find these foods attractive because they provide them with nutrients.

Conversely, natural objects that were dangerous, e.g. poisonous, have evolved to be unattractive to humans and animals, which is exactly why they have evolved to be poisonous to us. Humans and animals, on their part, have evolved to find poisonous natural object unattractive as well. This is congruent with the evolution of thorns, and the human preference for curves over sharp lines.

In general, we can say that the human experience of beauty and ugliness has been an evolutionary adaptation to the environment we and the species we evolved from used to live in. It incentivises behaviour that provided an evolutionary advantage. Specifically, it motivates us to be attracted to some (e.g. nutritional) things and repelled by others, such as dangerous things that might wound us. This is an important insight, because it could be useful in deciding what empirical research projects to undertake. Objects that map well on the above should be researched for their potential beauty.

Conclusion

There exist human universals in the domain of beauty, which has consequences for how we perceive architecture. Apart from the multiple types of symmetry that universally appeal to our aesthetic preferences across the globe, there exists an innate human need for ornament in the built environment.

Within the domain of ornament, some forms possess ‘universal’ beauty, stemming from our evolutionary history. These include foliage, flowers, human and animal representations, and, more abstract, spirals and curves. Many more may exist, but an entire overview of those that are known exceeds the purpose of this series. Moreover, many more universals may exist which are not known to man, but as will be shown in the next chapter this need not be an issue. The central takeaway is important here: Our aesthetic preferences for symmetries and (specific types of) ornament are innate and universal in our species.

This is an important realisation, as we will see later in this series, when we examine the merits of modernism, or more accurately the lack thereof. Let us first look at another important factor in the experience of architectural beauty: The position of the viewer.

Click here for the next article of this series.

Ward, J., Historic Ornament, published in 1897

Sussman, A., Cognitive Architecture, published October 2014, Taylor & Francis Ltd

According to the ‘Global Flower and Ornamental Plants Sales Market Report 2021’, published by Precision Reports on 4 March 2021, retrieved on 15 September 2021 from http://www.precisionreports.co/global-flower-and-ornamental-plants-sales-market-17522942

Retrieved on 15 September 2021 from https://news.psu.edu/story/141228/2008/01/21/research/probing-question-why-are-flowers-beautiful

Ward, J., Historic Ornament, published in 1897

Ward, J., Historic Ornament, published in 1897

Sussman, A., Cognitive Architecture, published October 2014, Taylor & Francis Ltd